A Tale of Optimization

I reimplemented Pygments in Crystal. It didn't quite go as I expected. I have already written about how I did it but that left a large part of the story untold. You see, I am using Crystal, which compiles to native code. And yet my reimplementation was slower than Python. That's not supposed to happen.

I decided to figure out why, and fix it. This is the story of how I made my software that looked "ok" 30x faster. Mind you, this is going to make me sound much smarter and accurate than I am. I ran into 200 dead ends before finding each improvement.

The First Problem (v0.1.0)

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine ../crycco/src/crycco.cr swapoff > x.html --standalone |

533.8 ± 4.4 | 523.7 | 542.9 | 18.80 ± 0.92 |

chroma ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -l crystal -f html -s swapoff > x.html |

28.4 ± 1.4 | 25.6 | 32.8 | 1.00 |

pygmentize ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -l crystal -O full,style=autumn -f html -o x.html |

103.5 ± 2.8 | 95.6 | 109.1 | 3.65 ± 0.20 |

That benchmark (like all the rest) is done using hyperfine and running each command 50 times after a 10-run warmup. Not that it needs so much care, just look at those numbers. Not only is tartrazine almost 20 times slower than chroma, it's also 3.5 times slower than Pygments. And Pygments is written in Python!

Even without comparing, half a second to highlight a 100-line file is ridiculous.

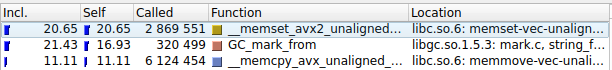

What's going on here? To find out, let's get data. I used callgrind to profile the code, and then kcachegrind to visualize it.

$ valgrind --tool=callgrind bin/tartrazine ../crycco/src/crycco.cr swapoff

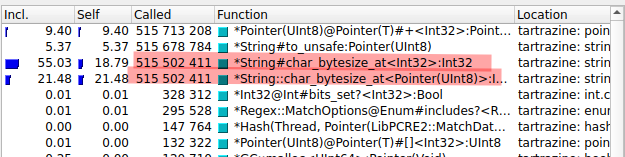

As you can see, some functions are called half a billion times and account for 40% of the execution time. What are they?

A string in Crystal is always unicode. The String::char_bytesize_at function is used to convert

an offset into the string from characters to bytes. That's because unicode characters can

be different "widths" in bytes. So in the string "123" the "3" is the 3rd byte, but in "áéí" the "í" starts in the 5th byte.

And why is it doing that? Because this code does a bazillion regex operations, and the underlying library (PCRE2) deals in bytes, not characters, so everytime we need to do things like "match this regex into this string starting in the 9th position" we need to convert that offset to bytes, and then when it finds a match at byte X we need to convert that offset to characters and to extract the data we do it two more times, and so on.

I decided to ... not do that. One nice thing of Crystal is that even though it's

compiled, the whole standard library is there in /usr/lib/crystal so I could just

go and read how the regular expression code was implemented and see what to do.

Ended up writing a version of Regex and Regex.match that worked on bytes, and made my

code deal with bytes instead of characters. I only needed to convert into strings when

I had already generated a token, rather than in the thousands of failed attempts

to generate it.

The Second Problem (commit 0626c86)

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -f html -t swapoff -o x.html --standalone |

187.8 ± 4.4 | 183.2 | 204.1 | 7.48 ± 0.30 |

chroma ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -l crystal -f html -s swapoff > x.html |

25.1 ± 0.8 | 23.6 | 28.5 | 1.00 |

pygmentize ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -l crystal -O full,style=autumn -f html -o x.html |

89.9 ± 4.7 | 83.6 | 102.1 | 3.58 ± 0.22 |

While better this still sucks. I made it 2.5 times faster, but it's still 7.5 times slower than chroma, and 3.6x slower than Python???

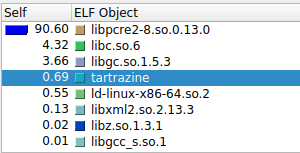

Back to valgrind. This time, the profile was ... different. The regex library was taking almost all the execution time, which makes sense, since it's doing all the work. But why is it so slow?

Almost all the time is spent in valid_utf8. That's a function that checks if a string is valid UTF-8.

And it's called all the time. Why? Because the regex library is written in C, and it doesn't know that

the strings it's working with are already valid UTF-8. So, it checks. And checks. And checks.

Solution? Let's not do that either. The PCRE2 library has a handy flag called

NO_UTF_CHECK just for that. So, if you pass that flag when you are doing a regex match,

it will not call valid_utf8 at all!

The Third Problem (commit 7db8fdc)

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -f html -t swapoff -o x.html --standalone |

30.0 ± 2.2 | 25.5 | 36.6 | 1.15 ± 0.10 |

chroma ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -l crystal -f html -s swapoff > x.html |

26.0 ± 1.0 | 24.1 | 29.2 | 1.00 |

pygmentize ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -l crystal -O full,style=autumn -f html -o x.html |

96.3 ± 7.7 | 86.1 | 125.3 | 3.70 ± 0.33 |

Yay! My compiled program is finally faster than an interpreted one! And even in the same ballpark as the other compiled one!

I wonder what happens with a larger file!

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine /usr/include/sqlite3.h -f html -t swapoff -o x.html --standalone -l c |

896.6 ± 71.6 | 709.6 | 1015.8 | 7.07 ± 0.58 |

chroma /usr/include/sqlite3.h -l c -f html -s swapoff > x.html |

126.8 ± 2.1 | 122.8 | 132.9 | 1.00 |

pygmentize /usr/include/sqlite3.h -l c -O full,style=autumn -f html -o x.html |

229.1 ± 4.5 | 219.5 | 238.9 | 1.81 ± 0.05 |

Clearly something very bad happens when my code processes larger files. I wonder what it is?

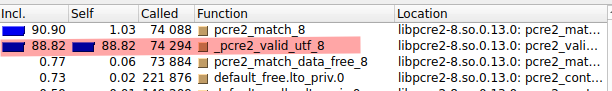

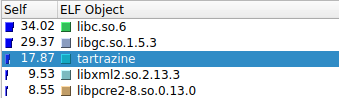

At first glance this is not very informative. So, most of the execution time

is spent in libgc and libc functions. That's not very helpful. But, if you look

a bit harder, you'll see the execution time is spent allocating memory. Hundreds

of milliseconds spent allocating memory

Yes, memory is fast. But allocating it is not. And I was allocating a lot of memory.

Or rather, I was allocating memory over and over. See that memcpy there?

This took me about a day to figure out, but this line of code is where everything became slow.

matched, new_pos, new_tokens = rule.match(text_bytes, pos, self)

if matched

# Move position forward, save the tokens,

# tokenize from the new position

pos = new_pos

tokens += new_tokens

That looks innocent, right? It's not. The tokens array is created at the beginning

of tokenization, and every time I find new tokens I just append them to it. BUT ... how

does that work? Arrays are not infinite! Where does it put the new tokens?

Well, when an array grows, it allocates a new, larger array, copies all the elements there and now you have a larger array with some room to spare. When you keep doing that, you are copying the whole array over and over. It's the cost you pay for the convenience of having an array that can grow.

Where was I calling this? In the formatter. The formatter needs to see the tokens to turn them into HTML. Here's the relevant code:

lines = lexer.group_tokens_in_lines(lexer.tokenize(text))

All it does is group them into lines (BTW, that again does the whole "grow an array" thing) and then it just iterates the lines, then the tokens in each line, slaps some HTML around them and writes them to a string (which again, grows).

The solution is ... not to do that.

In Crystal we have iterators, so I changed the tokenizer so that rather than returning an array of tokens it's an iterator which generates them one after the other. So the formatter looks more like this:

tokenizer.each do |token|

outp << "<span class=\"#{get_css_class(token[:type])}\">#{HTML.escape(token[:value])}</span>"

if token[:value].ends_with? "\n"

i += 1

outp << line_label(i) if line_numbers?

end

end

Rather than iterate an array, it iterates ... an iterator. So no tokens array in the

middle. Instead of grouping them into lines, spit out a line label after every newline

character (yes, this is a bit more complicated under the hood)

There were several other optimizations but this is the one that made the difference.

The Fourth Problem (commit ae03e46)

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine /usr/include/sqlite3.h -f html -t swapoff -o x.html --standalone -l c |

73.5 ± 5.9 | 67.7 | 104.8 | 1.00 |

chroma /usr/include/sqlite3.h -l c -f html -s swapoff > x.html |

123.1 ± 2.7 | 117.5 | 130.3 | 1.68 ± 0.14 |

pygmentize /usr/include/sqlite3.h -l c -O full,style=autumn -f html -o x.html |

222.0 ± 5.9 | 207.8 | 239.4 | 3.02 ± 0.26 |

Finally, tartrazine is the fastest one. On a large file! By a good margin! But is that all there is? Is there nothing else to improve? Well, no. I can do the same trick again!

You see, the formatter is returning a String by appending to it, and then we are

writing the string to a file. That's the same problem as before!. So, I changed the

formatter to take an IO object and write to it directly.

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine /usr/include/sqlite3.h -f html -t swapoff -o x.html --standalone -l c |

70.3 ± 1.8 | 65.6 | 73.8 | 1.00 |

chroma /usr/include/sqlite3.h -l c -f html -s swapoff > x.html |

122.2 ± 3.0 | 116.6 | 131.1 | 1.74 ± 0.06 |

pygmentize /usr/include/sqlite3.h -l c -O full,style=autumn -f html -o x.html |

219.4 ± 4.4 | 212.2 | 235.5 | 3.12 ± 0.10 |

As you can see, that still gives a small improvement, of just 3 milliseconds. But that's 5% of the total time. And it's a small change.

And this is where diminishing returns hit. I could probably make it faster, but even a 10% improvement would be just 7 milliseconds on a huge file. If I were GitHub then maybe this would be worth my time, but I am not and it's not.

And how does the final version compare with the first one?

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

bin/tartrazine-last ../crycco/src/crycco.cr -f html -t swapoff -o x.html --standalone -l c |

16.1 ± 1.1 | 13.1 | 21.8 | 1.00 |

bin/tartrazine-first ../crycco/src/crycco.cr swapoff |

519.1 ± 5.4 | 508.1 | 533.7 | 32.29 ± 2.23 |

A speedup factor of 32.3x, for code that had nothing obviously wrong in it. I'd say that's pretty good.